Cultural Restitution

SHARE ARTICLE

Britain has granted an export licence for a gold finial plundered by British troops from the throne of Tipu Sultan, the 18th century Indian ruler of Mysore. This means it can now be sold to a collection outside the United Kingdom. But it’s unlikely to return to India.

Despite a growing number of Indian citizen activists who believe all Tipu Sultan’s looted treasures should be returned, so far India has made no effort to exploit this opportunity and negotiate an alternate sale. Unlike China, where wealthy individuals are willing to step in and purchase looted treasures on behalf of the state (in China, restitution is a constitutional obligation), there is no force of wealth ready to buy back India's cultural heritage.

Speaking to Returning Heritage, Anuraag Saxena, a founder of India Pride Project, the global network of volunteers pressing foreign governments to return India's cultural heritage, explained the Indian approach is premised on conversation. “I’d be delighted if there are certain wealthy Indians that consider it their responsibility to buy these stolen objects and bring them back,” he said. “But I think a more sustainable equilibrium is one based on conversation, on morality, on decency, on shaking hands and agreements”.

There can be no doubt of the national importance this gold finial has to both countries: to the history of British imperialism and to the cultural legacy of Tipu Sultan (1750-99), who built a sophisticated court around his palace at Seringapatam in the Southern Indian state of Mysore. Tipu’s court attracted the finest artists in metalwork and jewellery and this finial is one of only a few fully documented examples of goldsmiths’ work from Southern Indian workshops.

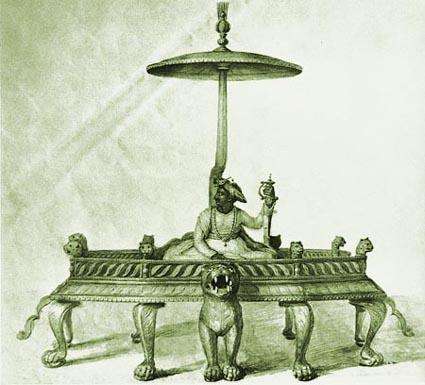

The finial is one of eight that originally adorned Tipu’s gold-covered octagonal throne. The head is set with rubies and emeralds with kundan-set diamonds and is mounted on a black marble pedestal. No finial recovered from this throne was decorated in the same fashion – each one is unique. It’s importance lies not only for the study of Indian royal propaganda, but also for illustrating the vibrancy of culture at Tipu’s 18th century court. Known as the ‘Tiger of Mysore’, Tipu adopted the tiger as his own personal emblem, featuring it prominently on all his regalia (“better to live a single day as a tiger than a thousand years as a sheep,” he once declared). Decorating his palace walls and armour with images of a tiger, he employed it imaginatively on every possible surface, including on other elements of his gold octagonal throne.

Gold Tiger Head Finial from Tipu Sultan's Throne

Regarded as the greatest threat to the rival interests of the British East India Company, Tipu was defeated by British troops at Seringapatam in 1799. Afterwards, his golden throne was “barbarously knocked to pieces with a sledge hammer,” according to eyewitness Pulteney Mein.

The governor of Seringapatam, Arthur Wellesley, expressed his desire to reassemble it and present it to King George III, “but the indiscreet zeal of the Prize Agents of the army had broken that proud moment of the Sultan’s arrogance into fragments before I had been appraised even of the existence of such a trophy” (Source: A. Buddle, The Tiger and the Thistle. Edinburgh 1999).

Following an episode of unprecedented looting, Tipu’s treasures were widely dispersed. The components of his throne were either sold off by the Prize Committee, which used the proceeds to offset the expenses of the war, or were held by the East India Company. Of the eight finials that decorated the throne, this is one of only five whose existence is known. One finial is at Powis Castle (which owns several other items of Tipu, including his royal tent), three others are in private collections, although the whereabouts of two of these is currently unknown. This finial, which has now been granted an export licence, was acquired by Thomas Wallace who was on the Board of Control of the East India Company (but who never went to India) and found its way to Featherstone Castle in Northumberland. It then disappeared before resurfacing at a Bonhams auction in April 2009 when it was sold for £389,600 to a private collector. It was exhibited in the 'Treasures from India' exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in 2014, before coming up for sale again at Christie’s in New York in June 2019 with an estimate of £350-500,000. This time it was withdrawn from the auction.

Tipu Sultan's Gold Octagonal Throne. Anna Tonelli

The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art met in May 2021 to consider this latest application for its export. They unanimously agreed that it met two of the three Waverley criteria, namely that its export from the UK would be a “misfortune” on the grounds (1) it was so closely connected with Britain's history and national life and (2) it was of outstanding significance for the study of royal propaganda and 18th century Anglo-Indian history. The Committee agreed a higher valuation than originally included with the application (£1,500,000 instead of £1,160,000), which almost certainly placed this object beyond the financial reach of any British public collection struggling with the legacy of Covid. However, after no offer or serious intent was demonstrated to purchase the finial, the Committee decided in February 2022 to issue the licence. Its future destination is unknown.

India’s claim this finial is “closely connected” with their country’s own history and national life is almost certainly as strong as the British claim - if not stronger, given the circumstances of its forcible removal. The absence of any other evidence of Tipu's golden throne surviving in India makes it especially unfortunate that negotiating a return to India has not been possible.

Saxena is an advocate that history belongs to its geography. In the case of this rare and important artefact, India's failure to step forward may prove an important opportunity lost.

Photo: Tipu Sultan, The Tiger of Mysore

Courtesy of ndtv.com

More News