Cultural Restitution

Eike Schmidt, director of Florence's Uffizi Gallery, is proposing an astonishing departure from accepted museum practice - returning religious works of art now held in museums and storerooms across Italy back to their original churches. Many have been held in museums since the end of World War II.

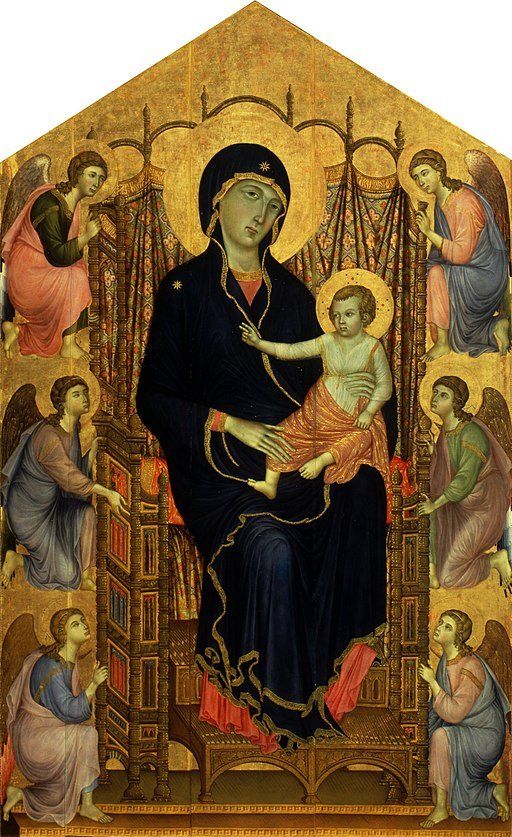

And he's not just talking about lesser works. He cites the specific case of the ‘Rucellai Madonna’ as the kind of work that should be returned.

The 'Rucellai Madonna' is a seminal 13th century gold-ground painting by the Sienese artist Duccio di Buoninsegna and is one of the major attractions in the Uffizi’s collection. Commissioned for the Laudesi Confraternity Chapel in the Florentine church of Santa Maria Novella in 1285, it was transferred to the Uffizi in 1948.

Speaking to The Art Newspaper , Schmidt said removing the painting from its original context takes away an essential part of its history and meaning. Viewing it in the context for which it was created is not just appropriate from an historical perspective, it can also connect the viewer with its spiritual significance.

His suggestion has been prompted, in part, by a reaction to the coronavirus crisis, but it's also part of a wider discussion underway at the Uffizi Gallery about returning more religious art to churches as a way of reaching out to wider audiences.

Well, there's an engaging idea! I suspect it will also resonate amongst the growing lobby who question the merits of de-contextualising cultural objects and who advocate selective repatriation.

After all, if it’s the right thing to return a medieval work of art to its original religious setting, why should other spiritually-significant items not be repatriated to the communities from where they were removed? And why should it not also apply to other culturally-significant objects stripped from their original buildings or location?

While it's noticeable that our smaller regional museums are leading the way by returning items to their original ‘context’, it's a great shame our larger museums continue to extol the merits of de-contextualising the heritage of objects in their collections. Their defence is to point out the advantages of offering new and different ways to engage with a particular heritage. A provocative argument that inflames rather than assuages the issues about context.

Interviewed in March 2019 for the Greek newspaper Ta Nea about the British Museum’s refusal to return sculptures removed from the Parthenon, the museum’s director Hartwig Fischer was completely unapologetic. “When you move cultural heritage into a museum, you move it out of context,” he said. “Yet that displacement is also a creative act”.

Few would agree with Fischer that stripping the Parthenon of its sculptures was a creative act, even though restoring them to their original location is equally unrealistic.

Fortunately for Schmidt, the Uffizi would face none of the legal constraints that prevent our national collections from returning contested items. As most of Italy’s churches are owned and maintained by the Fondo edifici di culto , a branch of the ministry of the interior, transferring any of the thousand or so religious works of art presently held in the storerooms of Italy’s state-owned Soprintendenze to another state body would be relatively straightforward.

But if Schmidt's idea does succeed, advocates for returning items to their original context will be hugely encouraged, our national museums will become more anxious.

Photo: Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Courtesy of publicdomainpictures.net

More News

Subscribe

Receive free updates on recent restitution news

Join the Newsletter

We will get back to you as soon as possible

Please try again later

CREDITS

Frieze block from the Temple of Athena, The Acropolis Museum, Athens

Acropolis photos courtesy of Anna Oikonomou

–

Site Design by

beckon.

All Rights Reserved | Returning Heritage